Elite: Dangerous comes at a time when the genre of flying around in spaceships has been essentially dead for years, but it's on the cusp of a revival. I've been making my way through the cosmos since the game was still in beta, and our preview went over the basics. The title contains a to-scale re-creation of the entire Milky Way galaxy. Currently, the game comes across as a bit empty, and while its universe is broad, it often lacks depth.

Elite: Dangerous immediately invokes some of my fondest memories from the Wing Commander series and the excellent Freelancer. Elite: Dangerous is being developed by essentially the same people who were behind the original games in the decades-old Elite franchise, and their passion for the genre clearly has not tempered with time. The game wears its Kickstarter success on its sleeve, as it targets hardcore space sim enthusiasts so directly that I doubt a major publisher would have chanced picking it up.

The title is best described as a space sandbox, in which you establish goals and make your own fun. The gameplay breaks down into combat, exploring, trading and, to a lesser extent, mining. There are no skill trees, and there are no abilities that need to be unlocked. The galaxy (with some exceptions) is fully open to you from your first launch, and what you can do is only limited by how many credits you want to throw at it. While players will undoubtedly have a favorite style of play, you can blast away at wanted ships to collect their bounties and then switch to some relaxing trading.

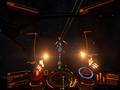

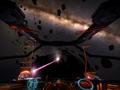

Before you get to any of that, you'll initially find yourself strapped into the cockpit of your starting Sidewinder, a small ship of limited means. All ships are generally the same when it comes to their arrangements and features, but it'll take a few minutes to get accustomed to the basics of flying your ship. While looking directly ahead, your interface looks akin to a big-budget version of space fighter games of yesteryear. The game tucks a lot of your ship's core functionality behind holographic displays to the sides of the cockpit, and those interfaces only spring open when you look that way. Clearly, the idea is to cement the idea of you behind an actual cockpit.

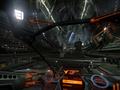

There's some amazing attention to detail here. Ship cockpits are immaculately designed and filled with details both functional and cosmetic. Rotating your ship through space sends accurate shadows of your cockpit frame across your console. Stations are filled with ambient movement and holographic advertisements. Your viewpoint is subtly affected by G forces as you maneuver, further immersing you into the world. Elite: Dangerous is absolutely one of the best-looking space sims ever made, and it's entirely due to Frontier's obvious passion.

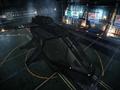

There's nothing about the game that should be considered "automatic." You control every action of your ship via one method or another. You don't just hail a station and pick an option to watch a docking cut scene; you're the monkey behind the stick lining up your approach through the station opening and craning your neck to find the right landing pad. The uninitiated probably views this as incredibly boring, especially after the hundredth time you've done so. I suspect most players feel that it somehow never loses its luster.

It's in this spirit that most of the game operates. Things take both time and effort, and you control the craft through all of it. Even a simple trade run requires you to navigate around the seemingly all-encompassing system star as you warp into a navigation beacon and line up your next jump. You glance over at your left display to see the results of a cargo scan or at your right to fiddle with ship module controls. There's a fine line before it starts feeling like busywork, but the game manages to dodge that pitfall.

Combat plays more along the lines of "aircraft in space" rather than a true Newtonian model of flight. You can choose to turn off Flight Assist (FA) to make the flight model a lot more Newtonian, but there are still some limitations. Ships not only have a maximum velocity that they can reach, but the actual maximum also differs depending on which axis you are traveling on. For example, you may be able to travel up to 400 meters per second forward, but if you turn off FA and spin backward to shoot at a pursuer, your speed bleeds off. The reasoning behind not going full Newtonian is likely due to gameplay balance, but it's worth noting for those who may expect it.

Ships have an ideal maneuverability speed where the rotational speed is best, which is represented on the HUD as a blue bar next to the throttle indicator. Often, you need to adjust your throttle to quickly track a target and then readjust it as the dogfight develops. Training your fixed weapons onto an enemy target can take some skill — doubly so for projectile weapons. Gimbaled versions of most weapons also exist to automatically track targets in front of you, but there are drawbacks in accuracy or damage output. This lets the game have a decently high skill ceiling, while still allowing players with less accuracy (or in less maneuverable ships) to be proficient in combat.

Combat is obviously resolved when one person gets away or is destroyed when their hull integrity is down to 0%, but there's more to it. Individual ship components can be targeted to the extent that your aiming/leading reticle calibrates to let you land shots on the specified module. This lets you try to target the thrusters of larger ships to give you more play in their blind spots, or you can blast at the frame shift drive to prevent targets from entering faster-than-light (FTL) travel. It can also lead to the pants-crapping moment when your canopy glass shatters into space, venting your cabin pressure and leaving you only with a few minutes of oxygen to return to a station for repairs.

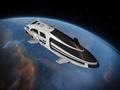

You'll have to get used to how the game has implemented FTL travel. In normal space, you use your thrusters to maneuver, dogfight, and dock with stations, but to move faster within a star system, you use your frame shift drive to accelerate to FTL supercruise speeds, so you can travel in minutes rather than weeks. During supercruise, your maneuverability is somewhat limited, but the player can still navigate around. As you do, so you can still see other ships and Unidentified Signal Sources zipping around the system. The USS beacons are the game's version of random encounters. Sometimes, it might be pirates attacking a hapless freighter, and other times, it might be a civilian funeral barge making its way through space. The funeral barge may even be a wanted pirate, and that makes the pursuit of bounty feel just a little bit dirty.

Even FTL travel doesn't mean you can stop paying attention to your radar. While you're in supercruise, other ships can attempt to pursue you and use an interdiction module to yank you out of it. When this occurs, you have to maneuver your ship to line up with a constantly moving escape vector. Fail to do so or cut throttle to submit to the interdiction, and your ship slows down to normal speeds in an uncontrolled tumble. In a nimble fighter, this means you may want to engage the target, but in a large freighter, this means you could be in a serious situation. Depending on the system status, you may be getting pulled over by system security for a routine scan, or you might be getting attacked by a pirate (player or otherwise).

To reach a new system, you don't have to travel to a waygate, such as the ones used in EVE or Freelancer. Instead, your options are limited by the range of your frame shift drive and the distance of nearby systems. If your frame shift drive can get you 15 light years in one jump, and the system is 13 light years away, you can get there in one jump. If your frame shift drive is weaker, you'll need to make intermediate jumps to reach the same place. You may not be able to get there at all if no shorter jumps exist. It makes travel a lot less restrictive, especially due to the in-game ability to plan routes, and it removes the idea of "gate camping."

If you dabble in trading, you'll quickly get accustomed to this mode of travel. Trade is surprisingly old school in implementation, and though in-game tools exist to help guide the player to profitable routes, they are often unreliable or wrong. Despite the unabashedly high-tech game world, your ship is unable to store the trade data from stations you've visited, which means a lot of successful trading boils down to keeping paper notes of which stations are supplying goods, demanding them, and at what prices. Third-party websites and programs exist to get actual data, but they're player-driven and can be out-of-date.

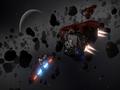

Mining is not unlike trading, with the main exception being the special hardware required to gather ore. Slap a mining laser and a refinery on your ship, and you can fly up to any asteroid in the game to slice into its contents. There is no way to know an asteroid's composition, short of cutting into it. As such, you'll prospect a few before finding one with worthwhile metals. Despite their massive size, asteroids contain fewer than a dozen chunks each, and (maddeningly) this content is completely different if two players tap into the same rock. In the early game, mining is a fantastic way to get some startup credits before you can afford a moderately equipped fighter or a solid starting freighter.

Exploration is another avenue of gameplay that you can pursue, but it's also one of the weakest. The game has billions of star systems, and at the current rate, it will take centuries before players find them all. If your ship is equipped with the right equipment, you can survey these unexplored systems, using your wanderlust within a system to track down planets, moons, and other points of interest. These systems lack any stations or NPCs, so exploring can be awfully lonely and uneventful.

It's worth mentioning that the game lends itself to — but does not require — head-tracking equipment. Obviously, the Oculus Rift is the biggest candidate for this, but other options, such as TrackIR or EDTracker, can also get you there. In my case, I sprung for the EDTracker, and even with its caveats, the effect of looking around a cockpit is a little surreal. It's one thing to press keys to lock your vision onto different panels; it's another entirely to move your head to glance at them or to look around to track an enemy target through different areas of your canopy glass. You can do the same with an extra analog stick on a HOTAS or even toggle controls with your mouse, but head-tracking integrates so well with the gameplay that it feels like it was meant for it.

There are a few major flaws that prevent Elite: Dangerous from becoming the cohesive sandbox that it clearly wants to be. The earning potential of the different styles of gameplay vary wildly, so some stages are either inaccessible or worthless to pursue. Chasing down bounties is great in the early game, but from mid-game and onward, the rate of bounties is a drop in the bucket compared to the money gained from trading. Mining is only viable firmly in the mid-game; early on, you don't have the funds to get the equipment and later on, you can't mine fast enough. From an income perspective, the credit-earning potential shifts so far into the favor of trading that anything else seems silly as more than a momentary distraction.

What if you simply want to heat up your guns and make a name for yourself via combat? While you will gain reputation with some factions and lose it with others, the system has little more dimension to it. Sure, higher rep prompts a faction to give you more choice missions, and low rep causes it to shoot you on sight. There should be more to it than that, as even the three main factions are more or less peacefully coexisting. It could just be that the cold war between them is still heating up, but it is all too easy to ignore, given how little they actually matter in the game. Developer-triggered events are held in some systems from time to time, but usually only in one or two systems at a time even though the game world has thousands of inhabited systems.

Another major issue with Elite: Dangerous is that, for all the talk of it being the first game in the series to feature it, multiplayer feels like a checkbox on someone's spreadsheet. You can't group up with players, and you can't trade with them. If two players shoot at a bounty, only the player who lands the killing blow gets the reward, and cooperating on missions is impossible. You can fly through the stars and engage random players by whatever manner you wish, but there are zero tools to interact with your friends. It's hard to recommend a game to someone I know when my only true interactions with them is to meaninglessly coexist in the same universe — or track them down and shoot them.

To Frontier's credit, multiplayer interaction is something that it plans to address in the upcoming "Wings" patch, which is slated in a few months. The biggest issue is the game's current inability to answer the simplest of questions: Why? Yes, you can perform various activities to pad your bank account or raise your rank based on many people you've killed or systems you've explored, but there is little to actually strive for in the game. Players are subject to the systems, but the game is coldly detached from player ambitions. As compelling as some of the gameplay loops are, you never get the impression that you are working toward something greater.

It sounds like I am harping on Elite: Dangerous, but it's a fantastic game and makes one wonder why space sims have been away for so long. For all of its polish in some areas, it has obviously unrefined aspects in others. For all the aspects that let you tell a story about the game, there's little to allow you to create in a story within it. During the first few weeks, the game will absolutely demand your free time, and you will gleefully engage. It just needs a lot more to sustain itself.

Score: 8.2/10

Reviewed on: Intel i5 2500k, 8GB RAM, nVidia GTX 660 Ti

More articles about Elite Dangerous

In Elite Dangerous is a space simulation game where you take a ship and 100 credits to make money legally or illegally - trade, bounty-hunt, pirate, assassinate your way across the galaxy.

In Elite Dangerous is a space simulation game where you take a ship and 100 credits to make money legally or illegally - trade, bounty-hunt, pirate, assassinate your way across the galaxy.